This production was created in collaboration with the inhabitants of South African townships. It was shortly after the fall of apartheid (in 1994 Nelson Mandela was elected president of South Africa). Artist Petr Nikl and I were invited to a festival with our production Solstice. On the spot, we learned that in addition to our production, we were supposed to conduct a workshop with the inhabitants of the townships to be able to participate in the festival. At the time, Johannesburg was a place with perhaps the highest crime rate in the world. Foreigners had to take a huge risk to enter the townships, which were originally built during apartheid as housing projects for black workers.

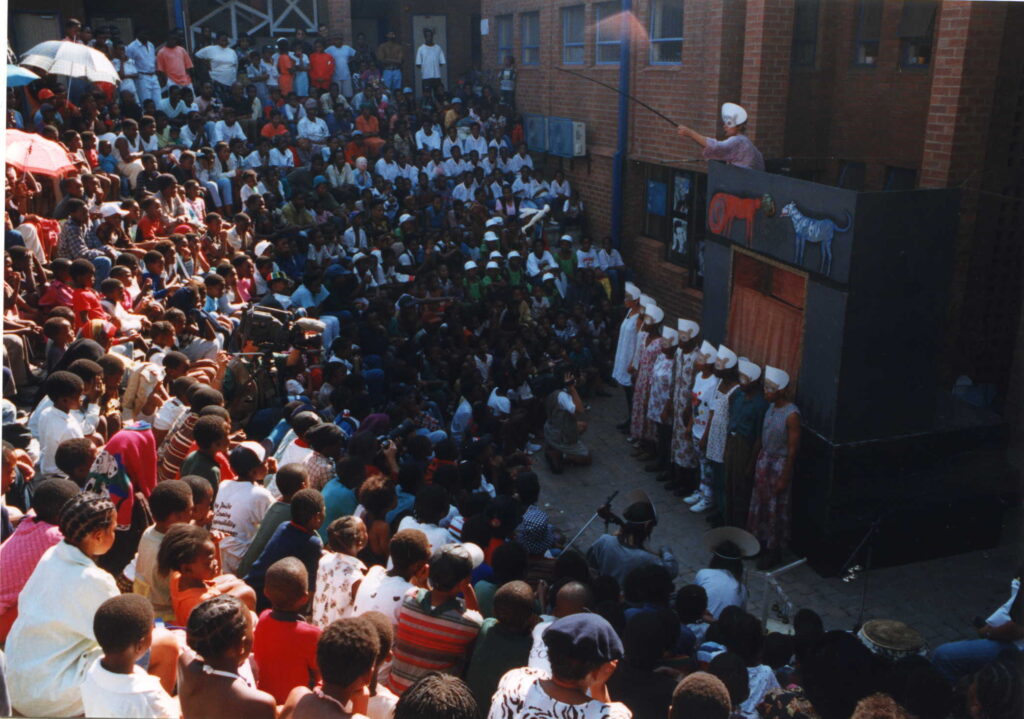

Solstice (South Africa)

photo: Ondřej Hrab

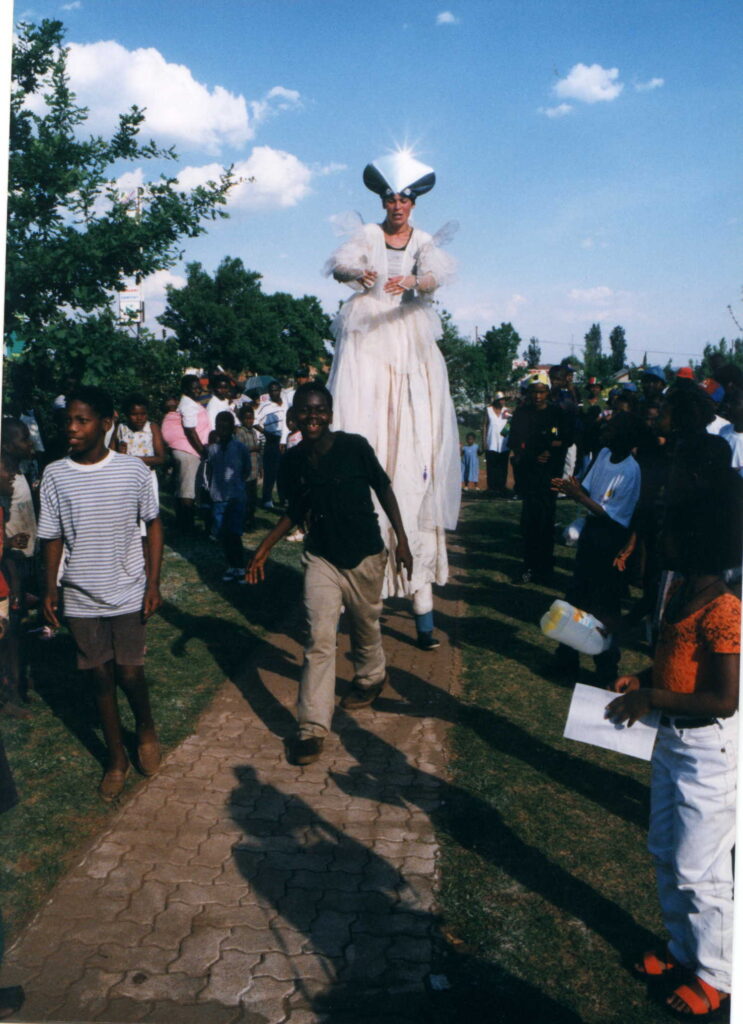

Solstice (South Africa)

photo: Ondřej Hrab

We found ourselves in a situation in which the people we wanted to engage in a short performance did not welcome us at all. They were not willing to meet us, let alone work together. They spoke English with a heavy accent, besides several of 11 different African languages. They said “Show us what you can do. If we don’t like it, we’ll go back home.” We looked at each other for a while in a room of a local cultural centre. We had not experienced anything like this before, we were completely untouched by what we now call social-specific theatre. We tried to speak, but it did not work. In a moment of despair, we pulled out Peter’s paper masks, fitted the rubber bands together, put on the masks, and turned into seven identical animals. Naturally, we all started moving like animals. After a very short time our colleagues from the townships were singing alongside traditional dance steps. We really enjoyed learning from them. In a circle we sang, moved, stomped with the rhythm that Matota, Agatha, Mike, Victor and Innocent created. We danced for a long time, trying not to ruin the magical harmony and synchrony of the steps.

Over the next three days, we set up a small show right in the centre of the township. I could even dare to run around on stilts. We had an audience including many black children and their parents. There were perhaps 1,000 of them. At that very moment, ethnic backgrounds were no longer important. We felt safe and enjoyed the moment together.

Key Takeaways:

In this complicated context, our joint activity served to overcome the obstacle of communication, created by different languages, ethnic backgrounds, and a difficult social context. To be able to work together, we had to build our practice only on the activities that we could do together: Dancing, singing, playing in masks, playing with objects. The theatre stage brought a new context. It created an artificial situation and we stopped being unwelcome guests and became partners in the game.

Useful Questions:

- Can theatre transform social stereotypes?

- What tools does it use to do this?